Written by Haley Boyce

Prose is art. The way a writer uses language to tell a story. It lacks formality yet requires attention to detail. Writers manipulate the structure of sentences to elicit an emotional response from their readers. When a writer tells a story in ordinary, everyday language they are giving you their best in prose.

Translated from its original form in Latin, prosa oratio, prose means straightforward.

This is not to say that prose is reserved for research papers or delivering scientific data, only that prose serves a direct purpose of telling something to the reader. What that something is, however, is up to you.

What are the Different Types of Prose?

Prose is one of those things that has so many examples that it becomes almost difficult to define. On one hand, the beauty of prose is that it really is everywhere you look. On the other hand, its definition can feel complex or ambiguous because of how expansive those examples can be. The following are some of the areas where you will (and have undoubtedly already) experienced prose.

There’s a big, fat chance that you’ve spent a good chunk of your life calling a book a novel just because it had a bunch of pages. Get ready for your mind to be blown: All novels are books, but not all books are novels. A novel is a fiction book with an approximate minimum of 200 pages.

Examples of prose include literally any and every fiction book that exists.

Prose in novels tells a story with all elements of plot, and the author works to create a story that moves you with their characters, conflict, word choice, and varied sentence structure. Whether an example of prose is good or bad is purely subjective.

Newspapers and other informational texts

Prose is present in any place where a story is being told, and that includes the news or any other form of printed information like journals or periodicals. For examples of prose in informational text, read the Los Angeles Times, the New Yorker, People magazine, or Yahoo news skim the surface of informational texts.

Let’s be real, not all speeches are great. Some hold an audience captive and leave them inspired to make some sort of change. Others are frightening in their ideals, out of touch with their audience, or just miss the mark completely. For examples of great speeches, check out TED talks, State of the Union addresses from past presidents, or (for a humorous tone) celebrity roasts.

Cinderella, The Little Mermaid, Jack and the Beanstalk, The Gingerbread Man, Hansel and Gretl, Rumplestiltskin . . . the list is infinite. All of these are examples of prose because they tell a story without conforming to meter, as poems do. Rather they have all elements of plot and a unique message and tone.

Conversation counts as prose! See how it really is everywhere?

Because prose is (again) informal, everyday language that tells a story, conversations that we have with our friends count as prose.

When the holidays roll around and you’re recounting that time your front tire blew out on the freeway, how you met your partner, or what happened when your dog saw a squirrel and wound up taking you on a walk around the neighborhood instead of the other way around – all of those stories are prose. The next time you tell a story out loud, think about the points in your story that you emphasize or embellish. These are elements that inflate your prose with the breath of life.

Meter, Meter Pumpkin Eater

Meter, Meter Pumpkin Eater

When it comes to writing prose, author’s compose without the restraints imposed on poetry. Where poetry tells a story by relying on syllables and word pronunciation to set the meter, prose is basically an all out free-for-all. To solidify your understanding of prose, compare some examples of the genres above with some of the following poems, which contain something prose does not: Meter.

- Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day, by William Shakespeare (iambic pentameter)

- How the Grinch Stole Christmas, by Dr. Seuss (anapestic tetrameter)

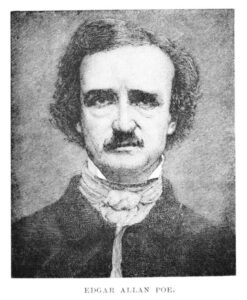

- The Raven, by Edgar Allan Poe (trochaic octameter)

- ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas, by Clement Clarke Moore (anapestic tetrameter)

- Because I Could Not Stop for Death, by Emily Dickinson (common meter)

- Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (ballad)

- Peter, Peter Pumpkin Eater, by Mother Goose (trochaic tetrameter)

What are the Elements of Prose?

As we briefly discussed above, prose should have the elements of plot in order to have any substance. The five elements of plot are:

Exposition: This is where the reader learns the basic gist of the story. The main characters are introduced, the setting is established (town, era, social class, etc.), and the reader gets an idea of what’s going on.

Rising action: This is where the reader learns the basic gist of the story. The main characters are introduced, the setting is established (town, era, social class, etc.), and the reader gets an idea of what’s going on.

Climax: Ask any teacher and they’ll tell you verbatim, “Climax is the most exciting part of the story.” But sometimes that’s hard to pinpoint when the story is an emotionally charged one that lacks as much physicality as an action-packed plot. Instead, look at the climax as the point in the story where the conflict starts to change. The main character’s view of the problem begins to look different and they might start to see the tiniest opening to work their way out of the problem they are in.

Falling action: Sometimes referred to as complications, the falling action is one or several small problems that keep the main character from reaching a resolution to their rising action.

Let’s say an adventurous main character finds themself at the top of a volcano when it begins to erupt (this is their conflict or rising action). First responders attempt to rescue them by extending a rope ladder, the main character hangs on tight. The responders begin to retract the ladder back into the helicopter but the combination of heat and weight is too much for the ladder and SNAP! The rope breaks.

Let’s say an adventurous main character finds themself at the top of a volcano when it begins to erupt (this is their conflict or rising action). First responders attempt to rescue them by extending a rope ladder, the main character hangs on tight. The responders begin to retract the ladder back into the helicopter but the combination of heat and weight is too much for the ladder and SNAP! The rope breaks.

This exemplifies falling action or complications because just when we think the main character has found a resolution to the conflict, a problem gets in their way. The rope ladder breaking is a problem, but it is small in comparison to the major conflict of the main character being at the top of a volcano when it begins to erupt.

Conclusion: This is often misrepresented as the end of the story. However, a conclusion (or resolution) is how the rising action is solved. So, while many stories near their end once the conflict is resolved, the author tends to use a few more pages or short chapters to tie up the loose ends of subplots. Where and how a conflict is resolved, and where it is placed in a story, is entirely up to the author.