I went through a phase a couple years ago just before beginning my master’s program in creative writing where I purchased books without knowing a single thing about them. Something about devoting my vulnerable reader’s heart to pages of the unknown felt risky and fun (Wild. I know.).

The result is a list of books and plays that left an impact so profound that I now feel I’ve found a kindred spirit in anyone who has read them, and am left stunned every time I learn that someone hasn’t. These are the types of books that have thousands of five-star reviews online but mentioning them in a workshop or dinner party will cock eyebrows and tilt heads.

Nobody is saying you shouldn’t also be reading Kafka and Bukowski and Burroughs (well, maybe not Burroughs), and chances are good you already are. But it’s also wise to shake off the notion that only the coffee shop crowd has the lock on what’s worth reading. Don’t play it so safe. Be a rebel and read a few titles that the cool kids are afraid to. It could change your life.

So, without further ado, I give you: The five best books you probably aren’t reading.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith

This is the very first book that I recommend to anyone who asks for something good to read. It’s a classic in the truest sense of the word, yet it somehow goes unread by most people I meet. I can’t even remember how this book wound up in my grasp the first time I read it, but I can remember exactly how it understood it made me feel. Set in 1912, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn follows the story of 11-year-old Francie Nolan, a first generation Irish-American growing up in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

This is the very first book that I recommend to anyone who asks for something good to read. It’s a classic in the truest sense of the word, yet it somehow goes unread by most people I meet. I can’t even remember how this book wound up in my grasp the first time I read it, but I can remember exactly how it understood it made me feel. Set in 1912, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn follows the story of 11-year-old Francie Nolan, a first generation Irish-American growing up in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Smith began as a playwright but found success as a novelist when she wrote the semi-autobiographical novel inspired by her own upbringing as the daughter of poor Irish immigrants. Therein lies the secret to her success.

A writer gives their best when they surrender their whole self to the art of storytelling.

It doesn’t have to mean that everything you write is based on real life, but it’s undeniable that the truth is often the small seed that grows into a whole story.

A Grief Observed by C.S. Lewis

This one made its way into my hands when my family lost our fourth loved one in as many years. As a cousin, my heart was raw. As a reader, I was desperate for words from someone who had walked the path of grief ahead of me to share what it was like. As a writer, I learned to leave it all on the page.

This one made its way into my hands when my family lost our fourth loved one in as many years. As a cousin, my heart was raw. As a reader, I was desperate for words from someone who had walked the path of grief ahead of me to share what it was like. As a writer, I learned to leave it all on the page.

Lewis penned A Grief Observed to map his pain after the death of his wife, Joy Davidman. Rare is the one who can process their heartache as it’s happening.

Lewis wasn’t thinking about his readers when he wrote this, and I think that’s the lesson to be learned here.

The conformity of publication and mass readership wasn’t his burden. He had a purpose while remaining simultaneously unknowing of what he would discover or become by the last page. Writers can learn from Lewis to allow the pain of an experience to steer the direction of our discovery. The result being a product that leaves both writer and reader transformed.

Smith began as a playwright but found success as a novelist when she wrote the semi-autobiographical novel inspired by her own upbringing as the daughter of poor Irish immigrants. Therein lies the secret to her success.

A writer gives their best when they surrender their whole self to the art of storytelling.

It doesn’t have to mean that everything you write is based on real life, but it’s undeniable that the truth is often the small seed that grows into a whole story.

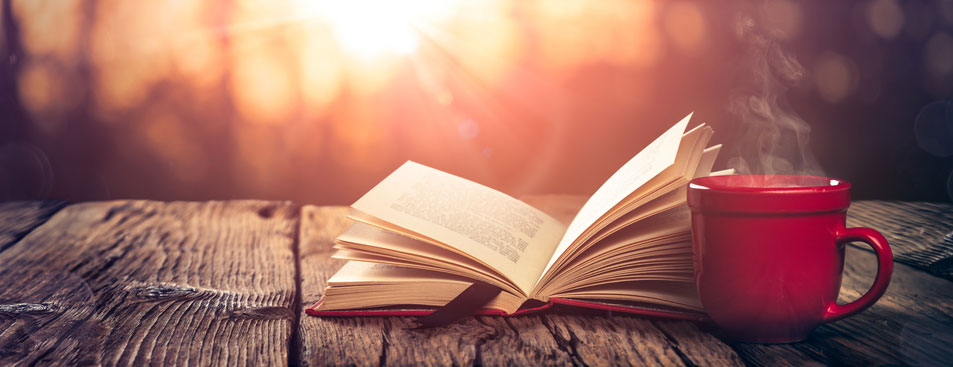

The Miniaturist by Jessie Burton

I chose this title for sentimental reasons – my best friend has a quirky affection for miniature scale models of just about anything. We read it together, sending texts to one another past midnights and plot twists.

I chose this title for sentimental reasons – my best friend has a quirky affection for miniature scale models of just about anything. We read it together, sending texts to one another past midnights and plot twists.

I came to The Miniaturist only knowing that I was a reader who wanted to be entertained, and I think that’s why it made me a better writer.

By reading without an agenda I was able to relax in a way that allowed me to take in every aspect of the story instead of searching for technique.

This is Burton’s work of art composed of steadfast research and adherence to the truth of 17th Century Amsterdam. Though her characters are fictitious, the time and place are so real and multidimensional that I promise you I can feel the wind on my face, hear the pup’s whimper, and sense the air growing thick with disdain and hypocrisy from a certain sister-in-law. If time machines are built with facts woven into lyrical prose, Burton is at the helm.

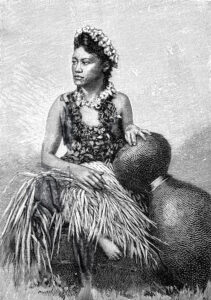

Hawaii by James Michener

Whew. Talk about an accomplishment. At over 900 pages thin as tissue paper, Hawaii took me over a month to read. By the time I reached the end, I had learned the history of the islands. It literally starts with the very slow formation of the rocky shores, but trudge on until you reach the history of the royal family, the arrival of missionaries, the whaling and sugar cane industries, the first Chinese laborers taken to the islands, leprosy, and an influx of tourists. By no means is this a textbook, but the fact-checking it’ll lead you to will make you smarter, more culturally aware, and have you booking an airline ticket.

Whew. Talk about an accomplishment. At over 900 pages thin as tissue paper, Hawaii took me over a month to read. By the time I reached the end, I had learned the history of the islands. It literally starts with the very slow formation of the rocky shores, but trudge on until you reach the history of the royal family, the arrival of missionaries, the whaling and sugar cane industries, the first Chinese laborers taken to the islands, leprosy, and an influx of tourists. By no means is this a textbook, but the fact-checking it’ll lead you to will make you smarter, more culturally aware, and have you booking an airline ticket.

In Hawaii, Michener sets the example of world-building. His storyline is so thoughtful and steadfast, so true to his characters that he even

includes a family tree at the end of the book. Writing organically has its merits, but I’m convinced that research and outlining are the cornerstone of creating a world where a reader can settle in for a while. Nobody does it quite like Michener in Hawaii.

Honorable Mentions Still Definitely Worth Your Time

A few others I couldn’t resist sharing. Take one, take them all – the wealth of inspiration will inspire your approach to the page. Promise.

A few others I couldn’t resist sharing. Take one, take them all – the wealth of inspiration will inspire your approach to the page. Promise.

Shopgirl by Steve Martin

He’s funny, he plays the banjo, he’s everyone’s fave funny man and movie dad. But holy moly, his writing is unparalleled. I dare you to find Steve Martin as you think you know him anywhere on the page. His words lend a lonely, haunting tone that is at once familiar and strange.

Half Broke Horses: A True-Life Novel by Jeanette Walls

Chronicles of Walls’s grandmother. Cancel your weekend plans. This book is quite literally un-put-downable. Inspiration for anyone who has a family member with stories to tell.

The Glass Castle by Jeanette Walls

A second on the list by Walls because she is just that good. Another one of those stories that makes you cringe at its truth but lean into it just the same.

This Time Together by Carol Burnett

If you’re at all into comedy and old Hollywood, you’re probably a fan of Burnett. If you’re already lost, give yourself the gift of a smile by searching for a video of Burnett and her bestie Julie Andrews in the 1962 sketch “Pratt Family Singers”. You’ll laugh. Then you’ll want to know more about Burnett. Learn it all by reading this particular memoir (she’s got a couple) about her life as a schoolgirl in Hollywood, her big break, and her friendship with Julie Andrews. Her voice is sentimental and funny and vivid. Truly inspiring.

A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen

Technically this is a play, but it’s equal parts too good and too ignored, so we must discuss. Written and set in 1879, “A Doll’s House” explores the very thing that society in any century considers a no-no for women: Discontent as a wife and mother. Ibsen is known as the father of Realism for the way he used his art as a medium to advocate for women’s rights. Oh, how I wish I could have taken a seat in the audience on opening night. To watch people shift uncomfortably in their seats as they were confronted with the notion that not all women want the same things. Can you imagine the side-eye happening that night? Ugh. I’d give anything to be there.

Technically this is a play, but it’s equal parts too good and too ignored, so we must discuss. Written and set in 1879, “A Doll’s House” explores the very thing that society in any century considers a no-no for women: Discontent as a wife and mother. Ibsen is known as the father of Realism for the way he used his art as a medium to advocate for women’s rights. Oh, how I wish I could have taken a seat in the audience on opening night. To watch people shift uncomfortably in their seats as they were confronted with the notion that not all women want the same things. Can you imagine the side-eye happening that night? Ugh. I’d give anything to be there.

That is the power of Ibsen. He shows us writers that art can transcend generations of audiences when the theme is unresolvable.

Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller

Miller’s Death of a Salesman is the male counterpart to “A Doll’s House”. There. I said it. We still have a lot to learn about one another as a species.

Miller’s Death of a Salesman is the male counterpart to “A Doll’s House”. There. I said it. We still have a lot to learn about one another as a species.

The fact that Miller wrote this play in 1949, 70 years after “A Doll’s House”, shows how little had changed with respect to one another’s assumed family roles. Or, from another perspective, it shows how failing to feel valued for what we contribute coupled with unchecked mental illness creates a deadly cocktail that can push things completely off the rails.

Miller tells the story with unabashed caricaturizing of family dynamics. It’s the kind of thing that makes a reader go, “Oh, shucks! He went there” and also makes a writer lean in and ask, “How’d you get there?”