At seven years old, my goal in life was to be able to read a chapter book. They just looked cool – thick with characters and unique worlds that, until then, had been read to me. I knew people reading chapter books must hold secrets to the world that they certainly weren’t sharing with me.

To me, readers were the epitome of cool.

Thirty-ish years later, I sit in front of a computer screen scanning lists of children’s books for my English students and for my own child. But I confess that I have caught myself on more than one occasion tossing books into my shopping cart because they mean something to me personally.

As a lover of all things wordy, I know that these stories are the finest form of art. That interpretations and sentimentality related to them cannot be forced upon another person. But I can hope, can’t I? That future generations will read the exact same words that shaped my childhood and begin to believe that family is made from acceptance, not DNA; that a group of seventh grade girls really can start a respectable business, or that teen boys can overcome stereotypes if they disregard the haters?

As a reader, this is what they taught me. As a teacher and as a mother, this is what I hope for my kiddos. As a writer, I aspire to reflect the influence each of these books has had on my life.

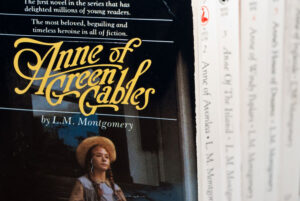

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery

Everything I know about reading and writing I owe to Anne Shirley. She is an orphan misplaced in a home known as Green Gables, unwanted at first because she is a girl and not the boy expected to help on the farm. Anne knows first-hand the imagination has the power to see you through some of the most unfathomable circumstances. The result is a heartfelt investment of time for readers, and a reminder for writers to lean into their imaginations without regard for the opinions of others.

Everything I know about reading and writing I owe to Anne Shirley. She is an orphan misplaced in a home known as Green Gables, unwanted at first because she is a girl and not the boy expected to help on the farm. Anne knows first-hand the imagination has the power to see you through some of the most unfathomable circumstances. The result is a heartfelt investment of time for readers, and a reminder for writers to lean into their imaginations without regard for the opinions of others.

Babysitters Club by Ann M. Martin

They’ve flipped the script in recent years, as this series is now printed as a graphic novel. Getting my hands on just one copy of this saccharine female empire is proving harder than my nostalgic heart can handle. Martin crafted a world that showed me in under 200 pages that a girl can be respected for her confidence and methodical thinking, that she can be both nurturing and in need of it herself.

They’ve flipped the script in recent years, as this series is now printed as a graphic novel. Getting my hands on just one copy of this saccharine female empire is proving harder than my nostalgic heart can handle. Martin crafted a world that showed me in under 200 pages that a girl can be respected for her confidence and methodical thinking, that she can be both nurturing and in need of it herself.

Each character was crafted to reflect the diversity of the children reading the stories. The result was a very clear message that any child from any upbringing can do big things.

Princess Smartypants by Babette Cole

Written for what is definitely the youngest target audience on this list, Princess Smartypants is an illustrated story that I can only imagine was inspired by the prompt, “What if a princess was the exact opposite of what she is expected to be?” Smartypants is happy with her life as a single woman who hangs out with her pets, rides a motorcycle, wears pants instead of a ballgown, and stays true to herself in spite of her parents telling her to “smarten up” and get married. For any story catch the eye of a reader it should be different from anything else that has been published before. I met with a group of agents who all said the same thing: We’re looking for what’s different. Cole answered that with a prime example in writing Princess Smartypants long before the female empowerment published in children’s books these days. Take that tip and run with it.

Written for what is definitely the youngest target audience on this list, Princess Smartypants is an illustrated story that I can only imagine was inspired by the prompt, “What if a princess was the exact opposite of what she is expected to be?” Smartypants is happy with her life as a single woman who hangs out with her pets, rides a motorcycle, wears pants instead of a ballgown, and stays true to herself in spite of her parents telling her to “smarten up” and get married. For any story catch the eye of a reader it should be different from anything else that has been published before. I met with a group of agents who all said the same thing: We’re looking for what’s different. Cole answered that with a prime example in writing Princess Smartypants long before the female empowerment published in children’s books these days. Take that tip and run with it.

The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

In a series of vignettes told from the perspective of 12-year-old Esperanza, readers of every age learn about empathy and family and what it feels like to be singled out. Esperanza is self-aware, made relatable through moments that humiliate and challenge her. Sometimes she rises above the shame, and sometimes she just doesn’t and that is what makes her fictitious self so very human. Sometimes lessons in writing come from reading through the mind of a child who is not always portrayed as happy.

In a series of vignettes told from the perspective of 12-year-old Esperanza, readers of every age learn about empathy and family and what it feels like to be singled out. Esperanza is self-aware, made relatable through moments that humiliate and challenge her. Sometimes she rises above the shame, and sometimes she just doesn’t and that is what makes her fictitious self so very human. Sometimes lessons in writing come from reading through the mind of a child who is not always portrayed as happy.

Not every story needs an over-the-top happy ending to be satisfying.

The Giver by Lois Lowry

If you’re in need of a text where symbolism abounds, this is it. Set in a dystopian society controlled by a board of elders, Jonas is a 12 year old who has recently been given the job title Receiver of Memories. Throughout the novel, we see him struggle to accept that the joys in life should be kept secret. Lowry shows us what it means to believe in the power of imagination as you write about a world that nobody knows about until it’s written down. The symbols she uses

If you’re in need of a text where symbolism abounds, this is it. Set in a dystopian society controlled by a board of elders, Jonas is a 12 year old who has recently been given the job title Receiver of Memories. Throughout the novel, we see him struggle to accept that the joys in life should be kept secret. Lowry shows us what it means to believe in the power of imagination as you write about a world that nobody knows about until it’s written down. The symbols she uses

The Boxcar Children by Gertrude Chandler Warner

The coolest thing about kid-lit is that it’s written by authors who treat children like the smart people that they are. Rather than cut corners to spare feelings, they tell stories of tragedy balanced with resilience as Warner does in The Boxcar Children.

The coolest thing about kid-lit is that it’s written by authors who treat children like the smart people that they are. Rather than cut corners to spare feelings, they tell stories of tragedy balanced with resilience as Warner does in The Boxcar Children.

Goosebumps by R.L. Stine

Checking out Goosebumps from the school library was a right of passage. Not much felt cooler than showing off the cover, silently telling everyone in class that you were brave enough to handle it. Stine’s gift as a writer is in the way he owned his niche – Scary but not terrifying. Spook sans gore.

Checking out Goosebumps from the school library was a right of passage. Not much felt cooler than showing off the cover, silently telling everyone in class that you were brave enough to handle it. Stine’s gift as a writer is in the way he owned his niche – Scary but not terrifying. Spook sans gore.

He knows his audience, as any writer should.

Hatchet by Gary Paulsen

We read this book as a class in fifth grade and afterward our teacher made a batch of rabbit stew right in front of my desk. I can’t think about Hatchet without thinking about how real the entire experience was. From the fiver page to the crockpot, Paulsen’s fictional world reads as realistic and horrific in every way.

We read this book as a class in fifth grade and afterward our teacher made a batch of rabbit stew right in front of my desk. I can’t think about Hatchet without thinking about how real the entire experience was. From the fiver page to the crockpot, Paulsen’s fictional world reads as realistic and horrific in every way.

The Witches by Roald Dahl

I’m convinced that much of an adult’s whimsical side can be attributed to reading Dahl books as a child. The vivid image of the witches removing their disguises to reveal their true appearances will stay with me until the day I die. It isn’t scary. Rather, it has more of a “can’t look away” vibe. In The Witches, Dahl’s shocking imagery is the stuff many writers aspire to.

I’m convinced that much of an adult’s whimsical side can be attributed to reading Dahl books as a child. The vivid image of the witches removing their disguises to reveal their true appearances will stay with me until the day I die. It isn’t scary. Rather, it has more of a “can’t look away” vibe. In The Witches, Dahl’s shocking imagery is the stuff many writers aspire to.

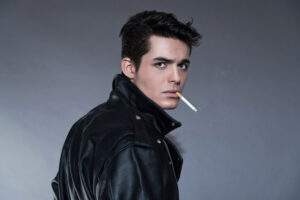

The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton

I’ve been a teacher for 15 years. In that time I have watched hundreds of students grapple with the definition of innocence, some have changed their style of dress to emulate the Greasers, and others have cried at the injustice of stereotypes. In a recent conversation with one of my Harvard professors, we discussed what makes a story last. The conclusion came down to theme.

I’ve been a teacher for 15 years. In that time I have watched hundreds of students grapple with the definition of innocence, some have changed their style of dress to emulate the Greasers, and others have cried at the injustice of stereotypes. In a recent conversation with one of my Harvard professors, we discussed what makes a story last. The conclusion came down to theme.

Stories with a timeless lesson are bound for a prominent place in bookshops and classrooms alike.

Mary Poppins by P.L. Travers

Talk about a masterclass in subtext! If you re-read anything you’re your childhood you’re bound to find things you hadn’t noticed before. Case in point: Mary Poppins. On the surface, she’s there to help a family find balance. Underneath it all, though, she’s got a life beyond nannying that we only get glimpses of. While there are a number of friendships revealed throughout the series, her most infamous one is with Burt. There’s an underlying tone to their relationship that remains unexplained and leaves readers wondering what the future holds for their bond. Knowing a bit about Travers, I feel convinced that any subtext was unintentional, and I guess that’s the point I’m trying to make.

Talk about a masterclass in subtext! If you re-read anything you’re your childhood you’re bound to find things you hadn’t noticed before. Case in point: Mary Poppins. On the surface, she’s there to help a family find balance. Underneath it all, though, she’s got a life beyond nannying that we only get glimpses of. While there are a number of friendships revealed throughout the series, her most infamous one is with Burt. There’s an underlying tone to their relationship that remains unexplained and leaves readers wondering what the future holds for their bond. Knowing a bit about Travers, I feel convinced that any subtext was unintentional, and I guess that’s the point I’m trying to make.

Sometimes the best material in our writing comes from what we leave unsaid.